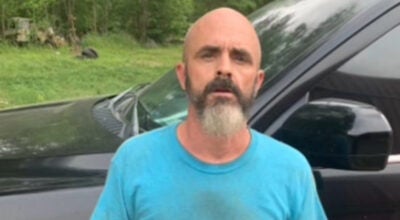

Ferriday mayor explains suspensions of police chief

Published 12:59 am Thursday, February 23, 2017

FERRIDAY — Following the second suspension of Ferriday Police Chief Arthur Lewis, Mayor Sherrie Jacobs said Wednesday she thinks the people deserve to know the details.

Lewis was suspended in December following two allegations of insubordination, and in February for a January incident in which Lewis instigated an argument between two officers, Jacobs said.

“My deepest desire is to assure the safety of our citizens and to continue to move Ferriday forward,” Jacobs said. “The people of Ferriday deserve a bright and prosperous future in a town where love reigns.”

Lewis, on the other hand, said at some point Jacobs turned against him and no longer wanted him to be police chief. Lewis said he thinks the matter is personal because Jacobs has a few people in her circle with agendas that may not be aligned with the town’s best interest.

The issues in the department, Lewis said, are related to Jacobs’ leadership and her undermining his ability to lead.

“I wish this mayor well, I really do,” Lewis said. “I believe the Lord put her there to help Ferriday. I pray she succeeds every night.

“But I think she has too many people in her ear with agendas. I believe, regardless, the right thing will happen. Time is going to tell — the truth always wins out.”

The first issue of insubordination came following months of budgetary problems, Jacobs said. Jacobs said Lewis kept hiring people, making purchases and allowing overtime to occur.

Jacobs said Ferriday Police Department’s payroll was 75 percent of the town’s total payroll. The department also had too many officers of rank, which Jacobs said caused friction and turmoil within the police force.

Eventually, Jacobs said, the finance committee met with the mayor and the chief to say that the town was $200,000 over budget, but Jacobs said Lewis refused to change spending habits.

“He continued to say he had to have the people he needed and the equipment he needed in order to do the job,” Jacobs said.

In October, after several board members reminded Jacobs that she was ultimately responsible for personnel and the budget, Jacobs said she issued a directive that there would be no overtime unless it was approved by the mayor.

Jacobs said she also studied the police department roster and eliminated some of the “fluff” positions that the town could not afford.

Jacobs delivered termination letters to the chief to give to the employees.

Lewis later returned two letters saying the people refused to accept them and allowed the people to continue working, Jacobs said.

“I did not call him out on the insubordination in an effort to continue working with him for our citizens,” Jacobs said.

During the Dec. 2 incident, Jacobs said she received a phone call from the police department that two officers were in a heated argument. One officer was following the other around and yelling and cursing.

Jacobs said the officer being followed called Lewis, who asked the officer to lock herself in the dispatch room and said he would come, but he never did.

Jacobs said Lewis elected to allow his assistant chief to handle it, but the assistant chief was out of town in Arkansas that Friday. Jacobs said both the assistant chief and the officer who was afraid for her safety contacted her, not Lewis.

With the assistant chief out of town and Lewis refusing to come, Jacobs said she acted because she was concerned flaring tempers and guns could lead to something bad happening.

“I told an officer to tell the one who had followed the other officer around yelling that he was suspended until I could talk to him on Monday,” Jacobs said. “On Monday, before I had a chance to see the officer, the chief told him to come on back to work because the mayor didn’t give him anything in writing.

“That was the second act of insubordination, and enough.”

Lewis said Jacobs did make it clear the town had no money. Lewis said he also did not have the power to hire, fire or order equipment, as an appointed chief.

Lewis said he could only make recommendations for hires, purchases or training, which he said were often denied by Jacobs.

Lewis said he gave officers ranks. In addition to a patrol captain, Lewis said he had a sergeant on all four shifts. Many of the officers were young, Lewis said, and the town did not have funds to properly certify their training, so he said he had a sergeant on each shift so one person could be responsible.

Lewis said in his years of law enforcement, setting up the shifts in this manner has been effective.

Overtime was a problem, Lewis said. Lewis said overtime is a problem at any police department.

“We understood Ferriday had a problem with money,” Lewis said. “But what else can we do? Stop policing because we ran out of money?”

Jacobs asked Lewis to deliver the termination letters, and Lewis said he did, though he said he told Jacobs he believed it would be better to let go three younger officers rather than the experienced officers.

Lewis said one officer accepted the termination, but two others said if the mayor wanted to terminate them, she could come do it. Lewis said he returned the letters to her and she accepted that outcome.

On Dec. 2, Lewis said an officer called him about a problem at the department, and he told her to get into the dispatch room, and that he would be there. Lewis said he spoke to his assistant chief, who he asked to handle it.

Lewis said the assistant chief was out of town, but had told him he was coming back and that he thought everything was under control.

After the assistant chief made it back, Lewis said the assistant chief claimed to have handled the situation. After that, Lewis said he did not hear anything else the rest of the night and he thought the situation was under control and saw no need to go to the station.

The next day, Lewis said he found out the mayor did go to the department and suspended an officer without telling him anything. And on Monday, after he had gotten statements from the officers involved, he compiled them and took them to Jacobs.

About an hour and a half later, Lewis said Jacobs delivered him the letter suspending him.

“It was the first time I had ever been suspended from a job,” Lewis said. “I asked her for due process. She had never had to reprimand me or had anything in my file that I knew of.”

Jacobs said during the suspension a consultant — John Cowan — had gotten the police department running smoothly.

“For those 30 days, the entire atmosphere at the department was peaceful,” Jacobs said. “There was much camaraderie with officers socializing in fellowship after work. I was asked to be present at every department meeting.

“My consultant explained police etiquette, provided training, and established rapport with the entire department without ever raising his voice. He often rode the streets during the day and night with his patrol officers to make sure they were not in need of anything.”

Following the suspension, Jacobs said she brought Lewis into her office and outlined her expectations.

“The bottom line was that the department was now in excellent shape, and I demanded that it stay that way,” Jacobs said. “The directive stated that if any of these directives were not followed, that would be grounds for another 30 days at home without pay.

“I explained that I had given him complete control of the department in July, and he nearly bankrupted the town.”

Jacobs said the second suspension occurred following an incident on Jan. 27, in which Lewis instigated an argument between two officers. Jacobs said she gathered statements from the officers and in February, asked the board of aldermen to terminate Lewis as she did not believe he was a good fit for Ferriday.

When the board refused to terminate Lewis, Jacobs said she suspended him for 30 days without pay.

Lewis said Jacobs had a 14-point directive. Lewis said he signed that she had read the directive to him, but that he did not agree with the expectations.

One issue he had was two people being brought on to be the liaison between the police department and the board and mayor’s office, Lewis said.

“That kind of puzzled me right off the bat,” Lewis said. “The board had just appointed police commissioners, (board members) Gail Pryor and Glenn Henderson.”

Lewis said two officers got into an argument, but he said he did not instigate it. Lewis said the argument was over officers stopping vehicles but not writing tickets, and one person within the department was upset and wanted patrol officers to be told to write more tickets.

Lewis said he did ask officers to write more tickets, but one officer, who Lewis says has a personal vendetta with the person who told Lewis officers were not writing tickets, guessed the source of the confrontation.

“In police work, you have to have facts or evidence,” Lewis said. “You can’t go off of he said she said — (Jacobs) did at that time.

“I will continue to do the right thing. I just hope and pray that everything comes out right. The whole community is what any leader should be concerned about.”

According to a conversation Jacobs said she had with an attorney and executive director of the Louisiana Municipal Association, the mayor is the administrative head of all departments including the police department and the chief only has whatever power is given to him by the mayor.

“It is incumbent upon me to see that my officers and dispatchers at the department are safe so they can protect and serve our citizens,” Jacobs said.