New program brings excitement to science at Cathedral

Published 12:31 am Wednesday, September 13, 2017

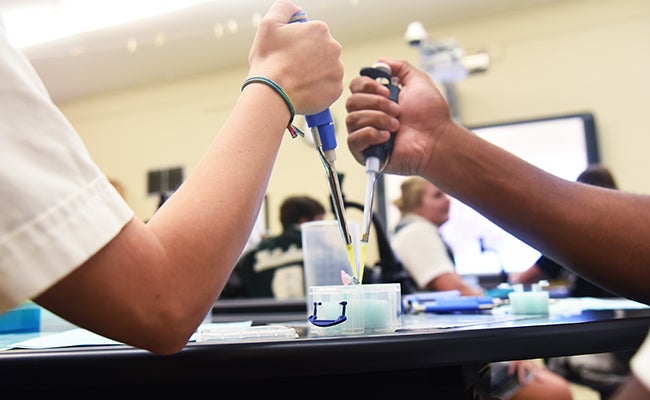

NATCHEZ — As Cathedral students carefully examined the habitats of tiny mealworms Monday, their teachers were busy analyzing and collecting their own data.

This year, Cathedral teachers Denise Thibodeaux and Jessie Wallace are participating in the Science Teaching Excites Medical Interest (STEMI) program, a partnership with University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson that flips the usual learning method to help students better understand lessons and instruct them on the health issues facing Mississippians.

The program is funded by the Science Education Partnership Award. Cathedral is one of eight schools in the state participating in the two-year program.

The technology-based program is designed to improve health literacy in Mississippi and get students excited about the medical field early.

STEMI is named for a severe heart condition, Thibodeaux said, because “the health problem in Mississippi is as serious as a heart attack.”

Thibodeaux was involved in a similar grant in 2010. When Dr. Rob Rockhold of the UMMC began STEMI last year, he invited her back to join.

She and Wallace spent four weeks this summer in Jackson learning a teaching technique called flipped learning.

The typical formula for classroom learning includes teaching, sending students home with homework to reinforce the lesson, and then testing later.

Flipped learning, Thibodeaux said, sends video, audio or Powerpoint lessons home with the students to study before covering the material in class, allowing them to learn at the pace which best suits each student.

This technique also gives students something to fall back on when testing comes. If a student needs a refresher on the material covered, he or she can access the lesson.

“You know in most classes there’s a couple of chapters that you never get to?” Wallace said. “We don’t have that problem. We’re covering at a higher pace and with a higher level of understanding.”

Thibodeaux, who has been teaching at Cathedral for 12 years, said her students seem more engaged in the material, and the new system allows her to do more hands-on experiments, such as the mealworm study.

“I want to do these hands-on things — these are the science processing skills they have to know to do well on the ACT and in their college classes — but they have to know the content, too,” Thibodeaux said. “How do you balance that? The flipped learning allows you to.”

In Wallace’s science and math classes, she has implemented statistics and mapping to show the real-world application of what students study.

Students are mapping food deserts and obesity data for the state of Mississippi, she said, making them understand how health issues affect the state while teaching them basic math.

Thibodeaux, who said she has never been fond of math, said she wished she had learned the subject this way in high school.

“If I had been taught math the way Jessie is teaching it … I would have loved it,” Thibodeaux said. “I think more students are going to be interested than they would have been.”

The research component of the program includes tracking a control group classroom that does not implement flipped learning and comparing interest levels, grades and graduation rates between the classes based on questionnaires handed out to both sets of students.

The control group in Cathedral’s instance is the health class of Mark McCann, who is also Wallace’s father.

No data is available yet for the classrooms, but Wallace Thibodeaux said they could already see a difference.

“I’m trying to expose them to things they’ve never been exposed to,” Wallace said. “When they see these kinds of things they realize, ‘I can really do this.’”