Parish reporter on quest for justice in 1964 killing

Published 5:24 pm Sunday, January 15, 2012

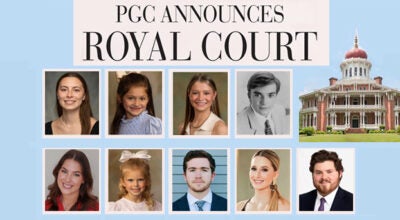

ERIC SHELTON | The Natchez Democrat — Stanley Nelson, above, stands on the foundation of Frank Morris’ shoe repair store on E.E. Wallace Boulevard Thursday afternoon. Nelson was honored in 2011 as a Pulitzer Prize finalist for local reporting for his investigative reporting on the murder of Frank Morris. The Concordia Sentinel photograph, at top, is of Frank Morris, center with visor and arms crossed, before his shop was burned in 1964 in Ferriday.

Concordia Sentinel Editor Stanley Nelson has carried a folded note from a stranger in his wallet for years.

The note, one of many from local people thanking him for information and his courage in trying to solve a civil rights murder that happened when Nelson was 9 years old, helps drive him to spend time after work and on weekends digging for justice.

Nelson, an employee at the weekly newspaper for 25 years and a Catahoula Parish resident, has read more than 15,000 pages of FBI files and interviewed more than 350 people on the telephone, at the office, in homes, businesses, street corners, cemeteries, nursing homes, hospitals and corn fields.

In four years he’s written more than 170 stories on the murder of Frank Morris. Morris died in 1964 after four days of suffering from third-degree burns on 100 percent of his body. The injuries came after a group of Ku Klux Klansmen burned down his shoe shop in the middle of the night, with him inside.

It’s notes like the one in his wallet, and phone calls from people like Morris’ granddaughter, Rosa Williams — who was 12 at the time of Morris’s murder — that keeps Nelson working on his off days.

“Once it becomes important to you, it’s not hard to do. You want to find out,” he said.

“These are really mysteries.”

Nelson’s motives are centered on justice for the family and for the community, not reproting fame. Still he was named one of two finalists for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for local reporting and was the recent recipient of the Gish Award from the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues for “courage, integrity, tenacity in rural journalism.”

“I don’t like to talk about that,” he said of the recognition he’s received.

Nelson was quick to segue that conversation to another.

“It’s been a lot of work by a lot of different people. It hasn’t just been me,” Nelson said.

Some of those who deserve credit, Nelson said, are members if the Syracuse College of Law Cold Case Justice Initiative, members of the Civil Rights Cold Case Project from around the country and Canada, 12 journalism students who have worked as interns at the Sentinel and dozens of people who helped him make contacts.

Nelson first learned about Frank Morris in February 2007, when co-worker Lesley Capdepon walked in the office on a Wednesday, in the middle of the rush to get the newspaper together to publish for the racks that afternoon.

Capdepon said she heard the FBI was opening some cold civil rights cases, and Nelson pulled up the list of names from the U.S. Justice Department website.

In the list of more than 111 cases he pulled up that day, Morris was one of a handful of local names.

Of the 111, representing 124 victims, only 39 cases now remain open.

Five local cases are among the 39, including the cases of Morris and Joseph Edwards, both in 1964 in Concordia Parish, Wharlest Jackson of Natchez from 1967, Clifton Walker of Wilkinson County from 1964 and Johnny Queen of Fayette in 1965.

But Nelson estimates more than a dozen civil rights era cases remain unsolved.

Nelson said he was drawn to Morris’ case the more he started to learn.

He talked to nurses and doctors about how Morris suffered living for four days until he died, and many expressed surprise he survived more than an hour.

“When I was in high school, we were coming home from a football game and came up on a horrible accident — a family of three died in a fire,” Nelson said.

He said he related his own memory of the accident to the death of Morris.

“I just thought, ‘How could you purposely kill people that way?’ I just couldn’t get that through my head.”

“What led those men to his shop that night?” he asked himself.

“And just importantly, are those men and others involved still among us, in the checkout line at Walmart or buying a soft drink at a convenience store?”

So he tried harder to understand.

Though interviews with Klan members, family of Klan members and family members and friends of victims, Nelson said he began to understand some more.

“What I found out was… these things are generational,” Nelson said.

Nelson said most of the Klan members were prejudiced, but they were not all killers.

“(The killers) were criminals,” he said. “And for two or three years, they did pretty well what they wanted to do.

“They were terrorists.”

And in every regional community — from McComb to Concordia Parish — on the verge of school integration in the mid ‘60s, the Klan was supported and abetted by a handful of bad cops, Nelson said.

The survivors, like Williams, also pushed him.

Williams, who was in her 50s when she called Nelson from Las Vegas in 2007, told him she had prayed her whole life for justice in her grandfather’s case, and she had learned more from one of Nelson’s articles than she and her family had in the past four-plus decades.

“The agony of the limbo, of not knowing, it’s sad,” Nelson said.

He said people talk about the murder even today and are still scared because some of the “bad people” are still around.

Telling the stories and solving the murders also tells a history of the area, Nelson said. But the history is something some don’t want to hear.

He’s received a fair number of phone calls from people asking him why he stirs up the past.

“Some people who do not like me writing about it, not only do they not want to read it, they don’t want anybody to read it.”

Nelson said he’s discovered that most who resent his efforts and want to bury the unresolved past usually have some type of unresolved sin their own lives to be worried about.

“I’ve never liked bullies. The men who killed Frank Morris and others during those days were ultimately little more than mean, hate-filled bullies who always hid in the shadows like cowards, often attacked at night in numbers and who spread countless lies about Frank and others as if that would justify their criminal acts.”

A year ago on Jan. 4, 2011, Nelson named a suspect in the Morris murder. The interviews with the suspect’s family matched up with the FBI interviews with Morris from the hospital before his death.

The suspect, a Richland Parish Klansman, denied it.

For a year, the case has been heard by a grand jury in Concordia Parish with the help of a U.S. prosecutor who is acting as a local assistant district attorney.

He said he’s learned that some of the less supportive readers seem to have a problem with sending an old man to jail, “which I find really strange.”

“If somebody had done something to my grandfather or uncle, I would hope someone would (revolve it),” Nelson said.

And in Nelson’s eyes, Morris was a valued member of the community, someone who worked hard, served a black and white clientele, paid taxes and provided for his family.

“Most everybody in Ferriday new Frank Morris, he was one of the most prominent black businessmen,” Nelson said.

Nelson said the burning fire pushing him to chase every lead on each case after his daily job is to see justice.

“Not just for the family, but for the community, too,” he said.

He said he’ll chase the cases as long as it takes, but the real enemy, other than the ones he’s searching for, is time.

“An enormously big issue is time itself,” he said.

In the Edwards case, for example, three witnesses and one suspect have died since the case re-opened.

“Time is running out.”

Nelson also said much of the region’s history has been largely unwritten and not been seen by younger generations.

“It’s our history. It happened. A lot of it is still unresolved,” Nelson said.

Unraveling the mystery, whether it unwinds from FBI files containing interviews with girlfriends and wives of Klansmen, or sitting on a porch with the victim’s family, is a simple responsibility Nelson assigned to himself when the cases dropped in his lap.

“I got to thinking, these families have lived with this for 40-plus years. That’s a long time,” he said.

“I felt like if we didn’t try to find out at the newspaper, who would?”