Veteran recalls Midway, WWII

Published 12:40 am Sunday, July 30, 2017

By Lyndy Berryhill

The Natchez Democrat

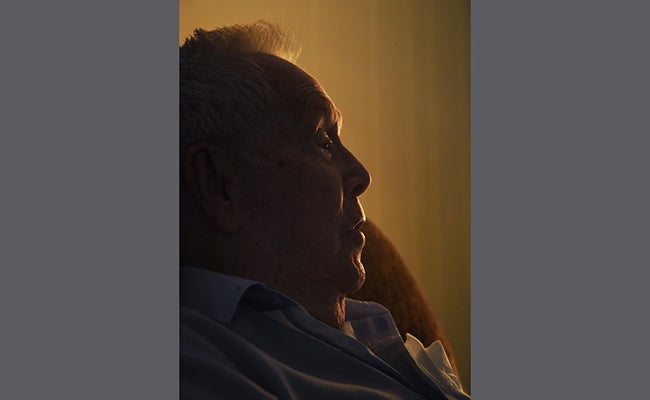

NATCHEZ — A man believed to be one of the last living Marines who fought in the Battle of Midway described the distinction with a simple word. “Lonely,” said William T. Hall, who celebrated his 97th birthday Saturday in Natchez.

Hall said he does not know for sure if he is the last survivor, but knows he has run out of friends he knew there. That’s last enough for him.

Although Hall has lost many friends to old age, he still has plenty of memories that are as pristine and clear as the tropical waters he sailed during World War II.

Hall said he still remembers arriving at the shores of Pearl Harbor nine days after the attack. He can still picture the blue waters that entombed big, beautiful battleships, many of which still contained men.

That day, and many more days of memories are long past.

Hall did not plan a party Saturday. He thought he might go get lunch by himself. Later he would thumb through his phone book and call up a few old friends. His wife died five years ago. His only son lives in Arizona.

Saturday morning, he watched the rain fall. Two people called to wish him a happy birthday.

He once belonged to a veteran’s group that reunited the fellow Marines who, among other vital duties, refueled and reloaded bomber and fighter planes in between skirmishes with deadly Japanese air force during the Battle of Midway. Only six months before, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor attack sunk four major battleships, damaged another 15 ships and damaged or destroyed 347 aircrafts. It took the lives of more than 2,000 people and wounded nearly 1,200.

The loss of Midway could have finished off the rest of America’s naval force. Due to courageous veterans, it didn’t. The Battle of Midway is largely considered a turning point for Allied victory in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Seventy-five summers ago, Hall was a 22-year-old. After two years in the National Guard and one semester in college, he signed up for the Marines on June 4, 1940.

Exactly two years later, Hall awoke to sirens and a skirmish of men headed to their stations. The Japanese had planned to take Midway with a similar strategy that had crippled the Navy, but Hall, his fellow Marines and some of the last naval forces fought otherwise to victory.

The battle was fought at sea and in the air.

Hall was grounded on Midway Atoll and waited until B-17 bombers would fly in. He would run out and supply the airplane with ammunition. The fuel tank was damaged at one point. Those on the ground had to bring fuel over in 55-gallon drums and pump it full, which took about 20-something barrels.

“It was just whatever had to be done at the moment,” Hall said.

When Hall was not refueling, he was keeping an eye out for shots taken at the island.

Only 307 American servicemen were killed in the battle. Hall was not harmed nor was his best friend who had enlisted in the Marines by his side the same day two years before.

The mess hall was a major casualty. The entire building was blown up. It only took a couple hours for men on the island to notice the cooler where the beer was kept had been hit and blown cans into the hot sun.

Hall and several others thought maybe they could place them on shores and the waves would cool them.

Hall said even though the water was cooler than the summer day, it was not cold enough to chill the beer enough. But it sufficed them for their long days of working into the night.

On June 7, 1942, the battle was won.

“It is still the best deployment I ever made,” Hall said.

Before he joined the Marines, Hall had spent his life around the United States with his family and the National Guard.

“I was a real child of the nation,” Hall said.

He was born in Denver, but moved to Green River, Wyoming when he was 5 years old with his parents, who were working for the railroad at the time. His father worked on the lines and his mother learned to be a waitress in the railroad cafe.

Hall said, back then, there were no dining cars. The train would stop for lunch every day.

He remembers his mother swiftly attending a feeding frenzy of tired, hungry passengers, serving 75-cent lunch plates to all before their train ride continued.

Hall loved Green River.

“I had so many exciting things happen to me there,” Hall said.

Hall ended up in Natchez in the 1970s after he and his second wife had visited the town and she fell in love with it. They bought a house downtown and moved in a year later.

Hall laughs when he thinks of his stubbornness, maybe the only trait, along with his humor, that has not aged.

Hall devoted his life to the Marines. He has a story for every day he served.

Some are funny, like when he drank torpedo juice. The fuel that propelled metal casings into submarines was 99 percent alcohol and didn’t taste too bad, he said, when it was the only liquor available.

Some are sad, like when he saw men smothered by coral debris after a Japanese bomb had hit near their post. Their lives ended in a trench that Hall had dug himself.

But Hall’s life continued.

Hall said he plans to reach his 100th birthday. His wish is to visit the Quantico museum, which details the deeds of Marines. It has a building dedicated to every war in which the Marines have every served in, he said.

People ask Hall how he has managed to live to 97. He tells them two things: good whiskey and the Marines.

Hall said one bottle of expensive Johnny Walker will last him months. It is not the quantity he drinks, but the quality which, like himself, has aged well.

Hall said he learned how to live, with a clean body and a clean mind, from the Marines.

He cannot imagine his life any other way.